By Jason Damweber, Deputy City Manager

Developing an annual recommended budget is the single greatest responsibility of a City administrator. It is a complex and ongoing task involving many stakeholders that culminates in the Council’s adoption of a document that reflects their priorities and the difficult decisions and compromises negotiated throughout the process. The annual budget is a tool used to plan for and reflect the balancing of resources with many competing needs.

As we gear up for the thick of budget season, we wanted to share information about the process, highlight challenges we expect to see, and begin engaging residents. After all, in the end, it is YOUR budget!

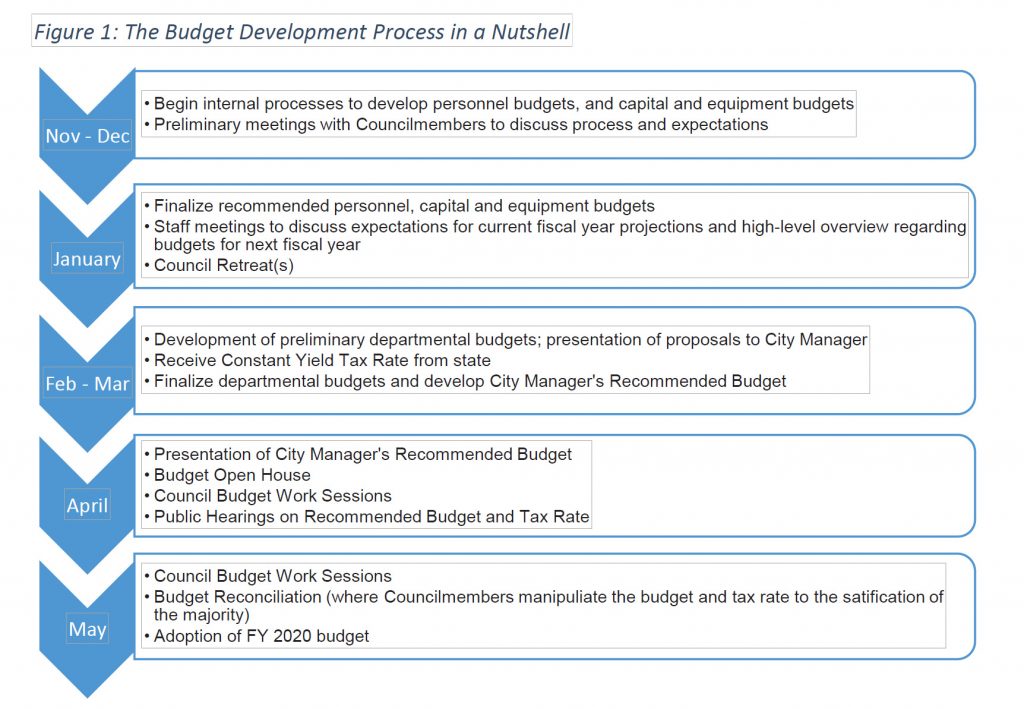

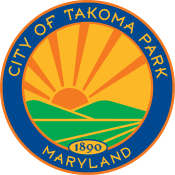

The Process in a Nutshell

While staff refers to late winter and early spring as “budget season,” the budget process is really ongoing throughout the year. We wrapped up and submitted the Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for Fiscal Year 2018 in October, the same time as we entered the second quarter of Fiscal Year 2019 and began planning for Fiscal Year 2020 (FY20).

In the past couple of months, staff committees have been meeting to review technology investment requests from departments and identify replacement needs of vehicles and other capital equipment. The City Manager and Deputy City Manager have been meeting with Councilmembers to gather feedback and ideas in preparation for both the upcoming Council Retreat meetings (where the Council establishes their priorities, including what they’d like to see in the upcoming budget) and the budget development process.

Looking forward, we’ll have the Council Retreat Meetings, staff work of developing preliminary departmental budgets, revenue projections, and development of a Capital Improvement Plan budget. Using this information coupled with the Constant Yield Tax Rate (more on this later), which we usually learn from the State in mid-February, we develop the City Manager’s Recommended Budget. The Recommended Budget reflects the costs of providing services and programs aligned with the Council’s priorities and the tax rate necessary to fund the work. In other words, where the money comes from and how it will be spent.

From there, Council will have a series of budget work sessions, a budget open house, a public hearing on the Recommended Bud- get and tax rate, and ultimately will adopt the FY20 budget and tax rate.

What We Know and Expect

Even if we “held the line” on the services and programs the City provides and did absolutely nothing new, the process to develop the budget would still be a challenge. In addition to expected increases in personnel and operating costs we have to project and account for, we also have to respond to changing assessments of home values and what those changes mean for the tax revenue that the City uses to provide services and programs. Additionally, we have to account for potential changes in revenues from sources other than property taxes, like funds received through the County or State. On the expenditure side, there are always changes that must be accounted and budgeted for. More on all of this below!

Revenues and the Budget

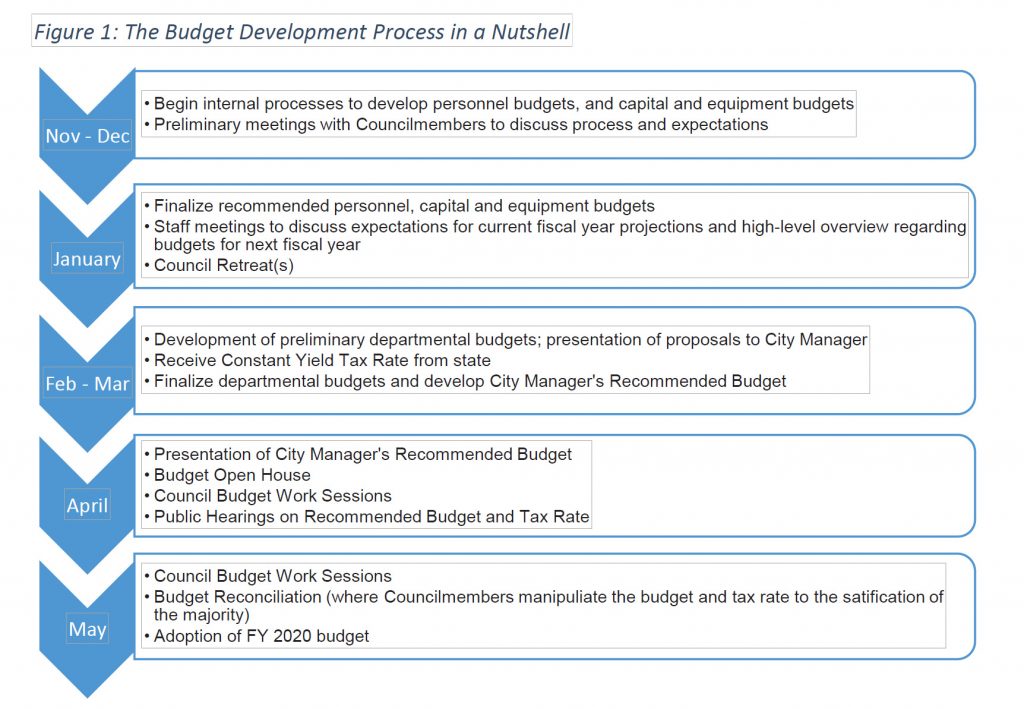

Revenues to the City come from a variety of sources, including but not limited to:

- Real property taxes: the taxes paid by property owners on the assessed value of their property

- Utility fees: taxes paid by public utilities on their property within the City

- Intergovernmental payments: payments to the City from different levels of government or government agencies, such as grants or reimbursement payments for services provided by the City that would otherwise be provided by the County

- Income taxes: the City’s portion of State-collected taxes applied to taxable income

- Charges for particular services: charges for particular City services that are not taxes, such as inspection fees, fees for Recreation programs, passport services, etc.

- Fines and forfeitures: funds received when the City institutes fines or realizes funds through the sale of forfeitures (the vast majority of these revenues are from fines related to speed cameras)

- Many people don’t realize that real property taxes – the taxes paid by property owners on the assessed value of their property– make up less than half of the City’s total revenues. In fact, only 39 percent of revenues in the current fiscal year’s budget are derived from real property taxes.

So what do we expect regarding revenues as we head into FY20? At this point it is difficult to say, but we should have a much better idea in late February. While intergovernmental revenues have been flat for some time (we believe we should be receiving much more from the County, but that’s the subject of a different article!) and are relatively easy to project, the City does not receive information on the total impact of changes in assessed property values until February. Around that time, we receive notice of the Constant Yield Tax Rate from the State. The Constant Yield Tax Rate is the tax rate the City would charge in order to receive the same (constant) dollar amount in property tax revenue. In other words, if assessments increase then the Constant Yield Tax Rate would decrease to net the same amount of revenue.

Given the regional trends we have been seeing, it’s probably pretty safe to assume that property values have increased. In fact, in the City of Takoma Park they have increased over 17 percent since FY14. If the trend holds true, then the Constant Yield Tax Rate will be lower than the current tax rate. However, pegging the City’s tax rate to the Constant Yield also means that we wouldn’t bring in enough property tax revenue to cover increased costs to provide services and programs.

Expenditures and the Budget

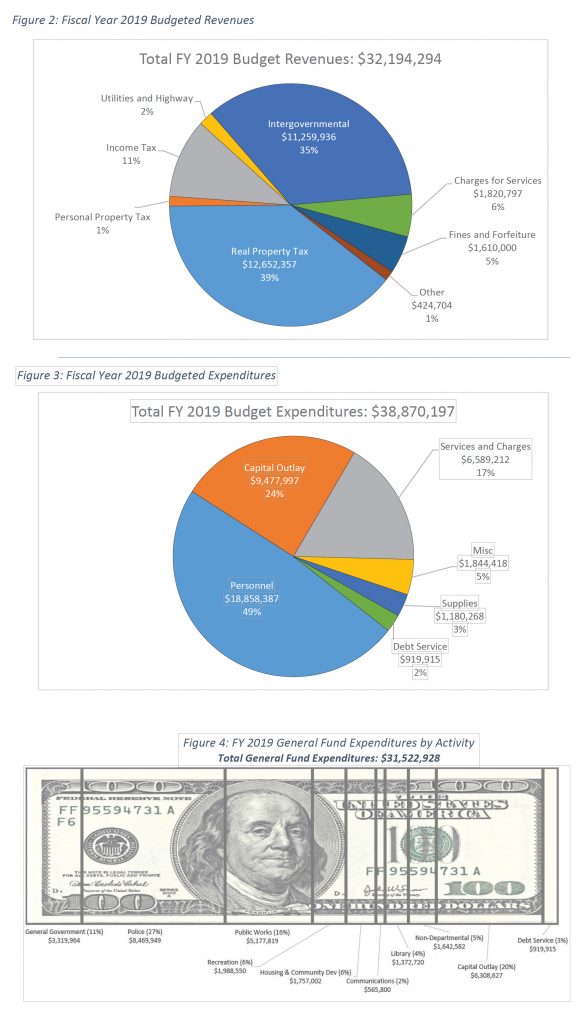

So now we have a sense of where City funds come from, but how are they spent? A good place to see the types of services and programs the City provides is the page on the City’s website called “City Services: Your Dollars at Work” (takomaparkmd.gov/about-takoma-park/city-services-your-dollars-at-work). If we look at the total budget as we did with revenues above, expenditures break down into the following key areas:

- Personnel: wages and benefits

- Capital outlay: costs for capital items like infrastructure and facility improvements, vehicle replacement, equipment replacement, technology improvements, park development, and stormwater management

- Services and charges: most operating costs other than those for personnel and capital outlay such as contracted services, licensing fees, non-capital small equipment, internal services (telephones, copying, postage), etc.

- Debt service: payments for the principal and interest on loans to the City

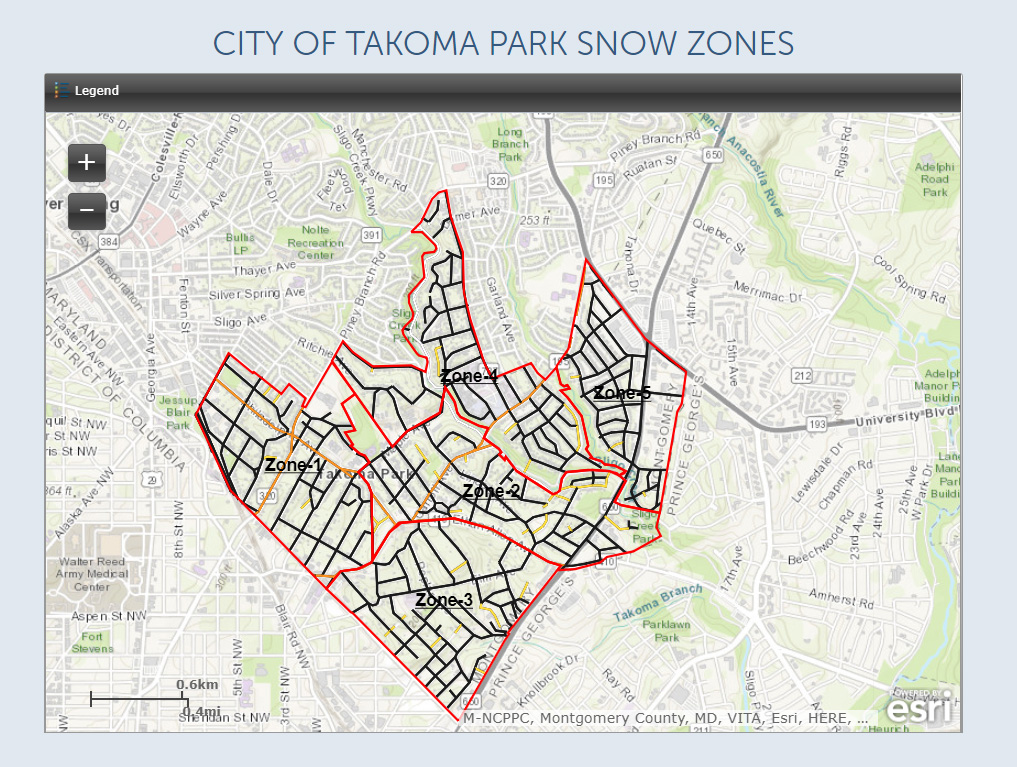

- Supplies: costs for office supplies, uniforms, vehicle fuel, construction and road repair materials, ice-melt, etc.

- Other: a catch-all for items that don’t fit neatly into the other categories, such as costs to conduct elections, conferences and training for staff, professional association membership dues, employee recruitment, special events and programs, etc.

If we look at expenditures from just the General Fund (that is, removing special revenues/expenditures provided for a particular purpose, the speed camera fund, and the stormwater management fund), total expenditures drop down to $31,522,928, and break down as indicated in Figure 4.

Something worth noting about these FY19 budgeted expenditures is that Capital Outlay does not typically make up such a large percentage of the budget. It can jump around a lot from year to year depending on what major projects are occurring or major equipment purchases are expected.

Personnel Costs

As noted above, even if we don’t add any staff, services, or programs, we can generally expect our costs to go up some each year. At the time this article was being drafted, it was not clear whether there would be a proposal to add or eliminate any positions. We also were not yet aware of the changes to costs for benefits like employee healthcare, which can fluctuate drastically from year-to-year. What we do know is that our staff members are our greatest assets and personnel costs make up about 49 percent of the City’s total budget, or 58 percent of the general fund budget.

So…if we assume that we will continue to have 168.86 Full Time Equivalents – the term used to represent the equivalent of the number of employees working full time – and hold the cost of benefits constant, we can expect to see an increase in personnel costs (wages) of somewhere in the ballpark of about three percent. This is a blend of a base increase and some merit pay. A three percent increase, which is in line with increases for local government workers nationally, equals some- where in the ballpark of $548,000. On top of that increase, it is reasonable to expect that employer costs for benefits will also increase slightly, though it is difficult to guess.

Operating Costs

Similar to personnel costs, it’s reasonable to assume that even if we continue to provide the same level of service and programs, the costs for doing so will increase. This is largely due to increasing prices for things like supplies, small equipment, contracted services, etc. That said, we are always looking for efficiencies, and occasionally are able to spend less than previous years on operating costs in certain areas. We also always have the option of discontinuing certain services or eliminating programs, but that could mean taking away something that residents have come to greatly appreciate or even rely on. This is all part of the annual balancing act. When we know more about Council’s expectations and any new priorities, departmental budget requests, and the Constant Yield, we’ll have a better sense of the extent to which we’ll need to hold the line, or change, eliminate, or add services and programs.

Debt Service

Debt service is one of the few areas where we have a good sense of what costs will be in the future. When we borrow money, we lock in a particular interest rate and can plan for spreading costs out over the term of the loan. For that reason, we don’t expect any surprises regarding our debt service payments on outstanding loans. Those loans include bonds used to pay for major Community Center renovations, construction of the Public Works facility, major transportation projects (Ethan Allen Gateway Streetscape and Flower Avenue Green Street), and planned Library Renovations.

Capital Outlay

As noted above, “capital outlay” refers to costs for capital items like infrastructure and facility improvements, vehicle replacement, equipment replacement, technology improvements, park development, and stormwater management. Most of the items in the “Capital Improvement Program” are things that we have known for at least a few years we would need to purchase.

For some items like vehicles and equipment replacement we may be able to realize some savings in the short term by pushing expenditures out if, say, a vehicle is in better shape than expected at the time we planned to replace it. On the “flipside,” sometimes vehicles and equipment may not last as long as we’d hoped. And for capital items involving construction, cost estimates developed one year could change significantly by the time a project goes out to bid. We have seen this recently as federal trade policies have caused dramatic fluctuations (mostly increases) in the costs of construction materials. A real-life and nearby example is the City of Gaithersburg’s planned public safety building. They expected to pay about $15 million on the project until very recently, and now they are looking at an $18 million price tag because of increases in the costs of steel!

There are also often new needs and expenditures that come up during the development process. Of course, these types of requests are viewed more favorably by the City Manager and Council when part of the justification for the expense involves cost-savings down the road.

Reserves

For many years, we have used an unwritten standard that there should be at least $3 million in unassigned funds in the General Fund at the time of budget adoption. That amount had been identified as an approximation of the funds needed to cover monthly cash fluctuations over the course of the fiscal year. It also provided a reasonable amount of cushion in the event of an emergency or disaster. However, over the years personnel costs and the overall budget increased to the point where $3 million was less than comfortable. The “industry standard,” per the Government Finance Officers Association best practices, is for unassigned reserves to be 17 percent of the total General Fund Revenue or Expenditure amount or a minimum of two months of regular operating expenditures.

In May of last year, the Council adopted a reserve policy stating that unless a special situation justifies a lower amount, they would adopt a budget that reflected this minimum reserve level (based on General Fund Revenues). In the event of a special situation, which would be explained in a public statement, they would strive to reach the mini- mum level within three years.

The good news here is that we ended FY18 with a larger unassigned fund balance than we expected. This was due to unexpected savings due to staff vacancies and postponement of certain major projects (for example, the Library Renovations which were put on hold temporarily when we learned that a new floodplain study would have required). The flip-side is that much of what was not spent last year will be carried over into the current year to be spent, so it’s not all actually “savings.”

The Bottom Line

Very few people like it when they have to pay more in taxes. Government officials (who are also human and also pay taxes!) are acutely aware of this fact. We do our very best to understand the needs, interests and priorities of members of the community and develop a budget that balances all these things. While it’s a task with many factors and considerations, there are really two primary, related levers when it comes to the General Fund: taxes and services. In a budget year where we can expect increases in the cost of providing services, tax revenue will need to increase in order to maintain service levels and programs. If we do not increase taxes, service levels will need to be reduced and/or pro- grams eliminated.

If the expectation is that the City continues to provide the same level of services and programs, there is little wiggle room in the budget to make changes or cuts. Our staff and budget are very lean. We do not have “fluff.” This means we cannot add services or programs without adding staff unless we discontinue other services or programs. A reduction in tax revenues will require cuts to services and programs. Cuts to programs usually mean cuts to staff. Most of our staff members wear a variety of hats, so if a position is cut, there could be ripple impacts to other services or programs. Additionally, we have debt obligations that must be met if we are to remain in good financial standing, capital purchases that must be made if we are to continue collecting solid waste and clearing snow, staff members who must be paid…you get the idea.

Hopefully you now have a better sense of the budget process and the many considerations that need to be weighed and balanced as it is developed. As we enter budget season, we welcome your feedback, input and ideas.

Additional Resources

The annual budget is a forward-looking planning document developed by staff that includes proposed expenditures and the revenue sources that will be used to cover those expenditures for a given fiscal year. The Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR), on the other hand, is backward-looking, prepared by independent auditors, and includes actual rather than estimated/projected dollar figures from the previous year(s). In order to get a full picture of the City’s financial standing and plans, one should refer to both the adopted budget document and the CAFR. These documents are available on the City’s Budget and Financial Documents page of the City’s website: https:// takomaparkmd.gov/government/ finance/budgets-and-financial-documents.

This article appeared in the January 2019 edition of the Takoma Park Newsletter. The Takoma Park Newsletter is available for download here.